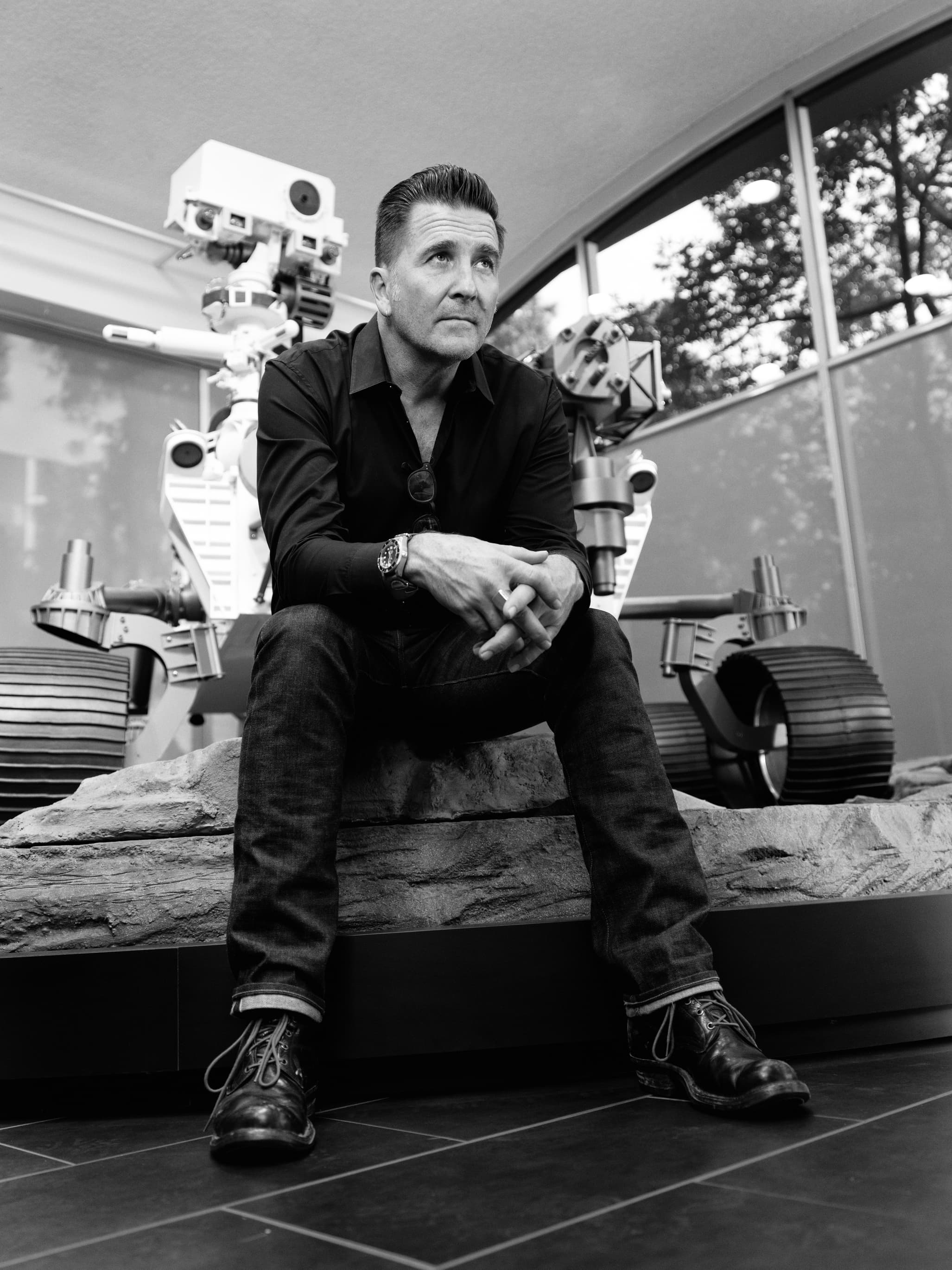

The first time I met Adam Steltzner, he strode into the Jet Propulsion Laboratory like a man who had just walked off a stage, a lead guitarist of interplanetary engineering. Dressed entirely in black, from his lace-up boots to the sharp-cut shirt that fit his lanky frame just so, he wore his hair in a dark, gravity-defying pompadour, a nod, perhaps, to another era of restless invention. But the real performance, the one that mattered, had already happened years before: a daring cosmic act that had played out 352 million miles away on the ochre sands of Mars.

Steltzner, the lead engineer of the Entry, Descent, and Landing (EDL) team for the Mars Science Laboratory, had overseen one of the most audacious maneuvers in the history of planetary exploration: the sky crane. It was, on paper, an almost preposterous idea, a Rube Goldberg machine designed not for terrestrial whimsy but for the dead-serious business of safely depositing a one-ton rover onto the Martian surface.

NASA had, of course, landed rovers before. The twin Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, had bounced onto the planet encased in giant airbag cocoons, a method that had served them well but wouldn’t work for something as large as Curiosity. And so, Steltzner and his team devised something radical: a hovering descent vehicle that, in its final moments, would fire retrorockets, dangle the rover beneath it on cables, and lower it to the surface like a delicate chandelier. Then, once its mission was complete, it would cut the cables and fly itself a safe distance away to crash into the Martian desert.

When he first explained this idea to colleagues, Steltzner was met with the kind of looks one reserves for madmen and visionaries. But he pressed on, convinced that this was the way, perhaps the only way, to accomplish the task at hand. Engineering, after all, is equal parts calculation and conviction, numbers and nerve.

It is strange to think that a man so dedicated to celestial mechanics once barely passed high school physics. Steltzner had drifted through adolescence in Marin County, playing bass in rock bands and moving aimlessly through the humid fog of California nights. It was a chance moment, one of those small, strange, turning points, that set him on a different path. Driving home one evening, he noticed that Orion had shifted in the sky from where it had been earlier. This puzzled him. Why did it move? He enrolled in a community college astronomy course to find out, and from there, his curiosity carried him through physics, engineering, and eventually, into the heart of one of the most prestigious planetary exploration teams in the world.

Over the years, Steltzner worked on several landmark missions, Galileo, Cassini, Mars Pathfinder, before stepping into his most formidable role yet with the Mars Science Laboratory. The stakes were high; the margin for error was zero. If any part of the descent sequence failed, Curiosity would meet its end in a catastrophic, multimillion-dollar fireball. The team rehearsed every contingency, simulated every failure, wargamed every what-if. But in the end, there was no escaping the moment when the vehicle had to fly itself, alone and untethered, through the perilous seven minutes of entry, descent, and landing.

When the signal finally arrived from Mars on August 5, 2012, confirmation that Curiosity had landed safely, Steltzner, in the control room, threw his head back and let out a deep, raw, exultant yell. It was, as he later said, a moment that burned itself into his consciousness, a triumph not just of engineering, but of imagination.

For all his rock-star bravado, Steltzner is ultimately a man of deep thought, capable of philosophical musings as easily as technical calculations. He speaks about uncertainty, about how embracing it is key to true discovery. “The nature of exploration is that you don’t always know what you’re doing,” he once told me. “You’re pushing into the unknown, and you have to be okay with that.”

It is perhaps this quality, this willingness to step forward into uncertainty, that makes him one of the defining engineers of our time. The sky crane worked not because it was safe, but because it was necessary. And necessity, as every explorer from Magellan to Einstein has known, is the mother of invention.

These days, Steltzner continues to chart new courses in the cosmos, working on projects that will one day return samples from Mars or send the next generation of rovers to even more distant worlds. But one gets the sense that he is, in some ways, still that young musician staring at the sky in wonder, still transfixed by the grand, gravitational dance of the universe. The only difference now is that he has made himself part of it.