There are moments in science when the universe shifts, not with spectacle, but through subtraction. A line erased. A definition revised. A conclusion reached that cannot be undone. Mike Brown has spent his career inside those moments, working at the edge of the solar system where certainty thins and evidence must speak for itself.

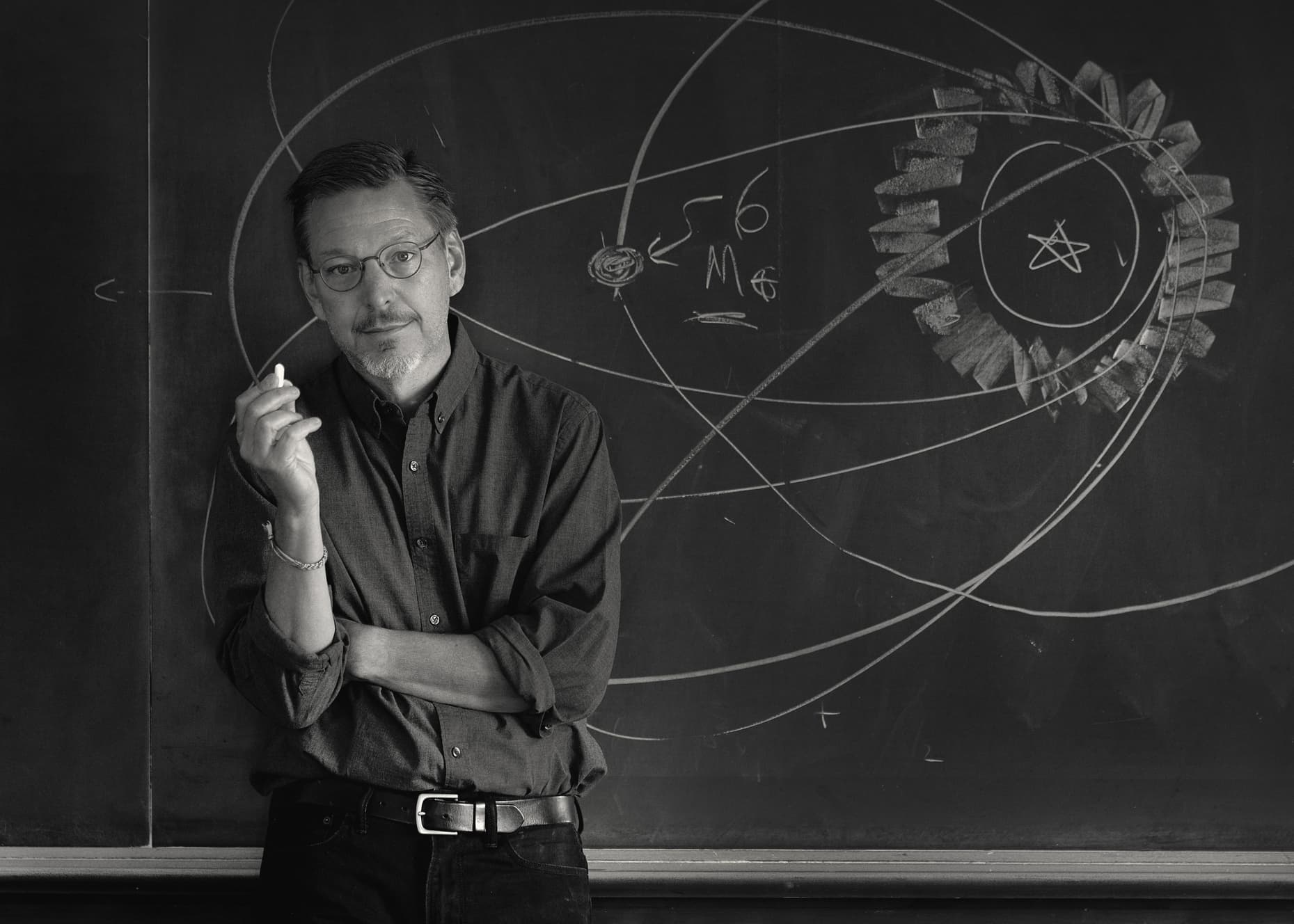

At the blackboard, sleeves rolled up, chalk dusting his hands, orbital paths stretch across the slate. Distant worlds loop and tilt, their motions bent by forces unseen. The drawing is not a picture of planets so much as a record of disturbance. Something massive is out there, shaping these orbits from far beyond Neptune. This is the search for Planet 9, a world inferred only through gravity, its presence written into the strange choreography of frozen debris in the Kuiper Belt.

Before Planet 9, there was Pluto.

In 2005, Brown discovered Eris, a distant object comparable in size to Pluto. The implication was unavoidable. If Pluto qualified as a planet, Eris had to qualify too. And if Eris did not, then Pluto did not either. The data offered no room for compromise. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union revised the definition of a planet. Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet.

The reaction was swift and emotional. Brown became a public villain. His inbox filled with outrage. Children sent angry letters. Even his daughter protested. The nickname stuck. Pluto Killer. But science does not operate by referendum. The evidence held.

After Pluto, Brown turned again to absence. He and his colleagues noticed a peculiar alignment among the most distant Kuiper Belt objects. Their orbits clustered in ways that chance could not explain. The simplest answer was also the most radical. A hidden planet, perhaps ten times the mass of Earth, exerting its influence from deep darkness.

Planet 9 remains unobserved. No image yet. No definitive detection. Brown is comfortable with that uncertainty. His career has been built on following what the data insists upon, not what anyone hopes to be true. If Planet 9 exists, it will eventually reveal itself. If it does not, the failure will still teach us something fundamental about how the solar system works.

Brown’s office at Caltech is crowded with books, plots, and images of distant worlds he has discovered, named, and reclassified. His old Twitter handle still reads @PlutoKiller, half joke, half scar tissue. But when he talks about the universe, there is no defensiveness. Only focus. Not the gaze of someone who took a planet away, but of someone still searching for the next one.